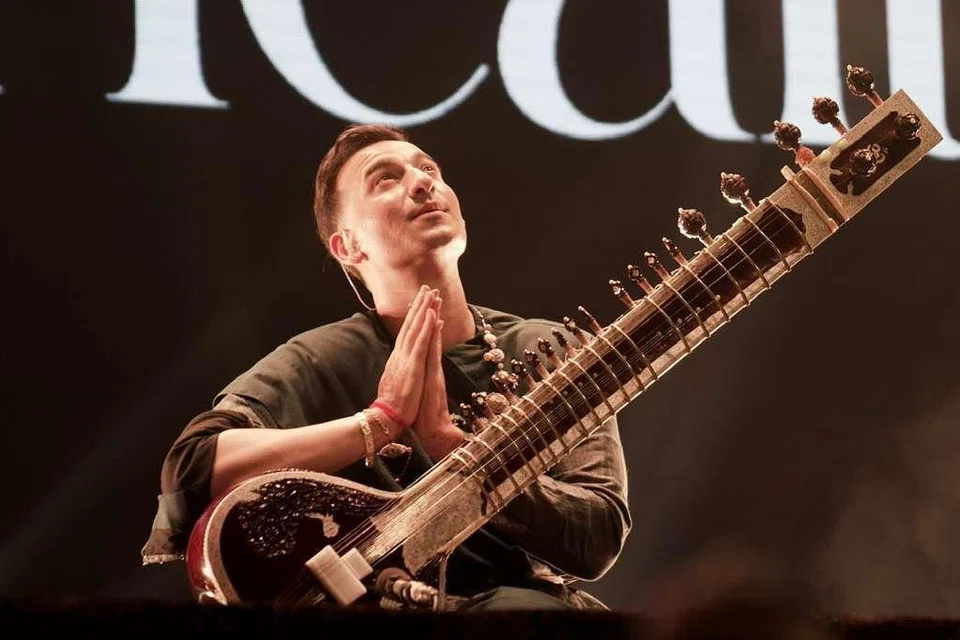

On Jan 25, Rishab Rikhiram Sharma will make his Singapore debut at the Esplanade Concert Hall, a venue known for hosting artists who straddle tradition and innovation.

For Mr Rishab, a sitarist trained in the deepest currents of Hindustani classical music, the performance arrives at a moment of acceleration.

“This year is looking to be a very interesting year for me and my musical journey,” he said. “There’s a lot of exciting stuff coming this year.”

Mr Rishab, 27, whose show is called Sitar for Mental Health, is a stickler for curation. “I am very finicky and involved in each and every thing,” he said, adding that the responsibility for delivering a smooth and engaging concert experience ultimately rests with him.

The current chapter of Mr Rishab’s career began during a period of personal loss. In late 2020, following the death of his grandfather, Mr Rishab found himself struggling with depression and anxiety.

“There was a point where I gave up music, and it got even worse for me. I was dealing with depression,” he highlighted. “I thankfully found solace in music.”

During the Covid-19 pandemic, Mr Rishab began holding informal sitar sessions on Clubhouse, an audio-based social platform that briefly surged in popularity. “I started playing my heart out in those sessions,” he noted. “Three people became six, six became twelve, it just kept snowballing.”

One evening, the virtual room reached capacity. “There were 4,500 people in the room,” Mr Rishab recalled. “That’s when I realised this community has potential.” That early audience has since followed him across platforms and continents. “They are still cheering the loudest,” he said.

Mr Rishab resists categorising his work as therapeutic, though he does not shy away from its effects. “I truly believe music should have a deeper meaning,” he said. “It’s more than just an audible experience.”

To truly make the sitar a conduit for peace, Rishab is turning to academia, seeking to understand how the instrument evokes happiness and tranquillity. “Now I’m studying what the sitar does to the mind,” he said. “I’m trying to understand brain waves and responses.”

In preparation for his upcoming show, Mr Rishab has consulted neurologists and mental health professionals, noting that while listeners often describe a sense of calm, there are few formal studies on the sitar’s cognitive effects. “There are no sitar-specific studies yet,” he said. “I’m just curious.”

Mr Rishab was born into the Rikhi Ram family – a renowned lineage of luthiers (instrument makers) from Delhi, India. The business was started by his great-grandfather, Pandit Rikhi Ram Sharma, in Lahore in 1920.

However, despite being closely associated with the sitar, he is careful to distinguish inheritance from inevitability. “Instruments didn’t fall into my lap,” he said. “My father truly believes instruments are sacred.” There was no expectation for Mr Rishab to participate in the craft simply because his bloodline was invested in it.

By classical standards, Mr Rishab’s formal training began relatively late. “I started learning when I was 11, whereas people usually start at the young age of 4 or 5,” he noted. Even so, he describes his relationship with the instrument as reciprocal rather than predetermined. “I feel like the sitar found me,” he said. “It picked me at the right time.”

Mr Rishab studied Music Production & Economics at Queens College in the City University of New York. For much of his early career, as part of his education’s influence on his taste, Mr Rishab occupied two musical worlds simultaneously – rigorous classical training and self-taught electronic production.

“I was learning deep classical music and making EDM beats at the same time,” he said. “I vibed with both.”

The reconciliation of those impulses, he said, came when he asked himself if it would make the 13-year old version of himself happy. That question is still a guide to his innovation process. “Classical music absolutely needs to be preserved,” he emphasised. “But we also have to look at scale.”

He is particularly critical of narratives that frame classical forms as endangered. “Presenting art as ‘dying’ doesn’t excite new audiences,” he pointed out. “I want to make classical music look cool.”

Trying to do that hasn’t come without its fair share of criticism, which he added, often arises from partial exposure. “People judge from viral clips, not the full experience,” he said. “If you’ve been to the show, you’ll understand that every part of the show is intentional.”

Despite appearances at institutions like the United Nations and the White House – where he became one of the first South Asian artists to perform at the latter’s inaugural Deepavali celebration in 2022 – “I sometimes forget that I’ve done these things,” Mr Rishab said, trying to stay grounded and focused on how to make the sitar more accessible.

When asked whether he worries about the ephemeral nature of show business, he said he finds reassurance in the enduring reverence accorded to maestros, regardless of age. While careful not to place himself alongside legends like Zakir Hussain, he hopes for a career of comparable longevity.“There’s no rush to be relevant,” he said.

Balance, he added, is non-negotiable. “Performing is work. Making music is how I spend my downtime,” he shared. As he prepares for his debut at the Esplanade, Mr Rishab speaks excitedly about his first foray into performing in Singapore. “The hall is historic and beautiful,” he said. “I’m excited to explore new territory.”