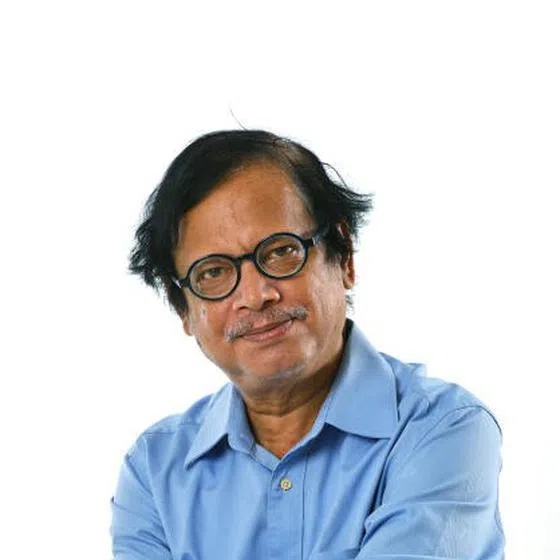

Professor Arijit Biswas is a busy man.

He has delivered more than 14,000 babies in his 35 years as an obstetrician, a profession that brought him to Singapore in 1991 after his medical studies and work in India and the United Kingdom.

The 69-year-old, who hails from West Bengal, is an eager Bengali who would love to have an adda with me, adda being a peculiarly convivial form of conversation between Bengalis that covers everything from good food and great art to political commitment and everlasting love.

Unfortunately, his schedule does not permit a meeting over indulgent tea and endless snacks – for there are babies waiting to be born – and so we meet at the National University Hospital in Kent Ridge.

He is Professor, Emeritus Consultant, and Clinical Director at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in the National University Health System and the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine at the National University of Singapore.

He was awarded the prestigious National Outstanding Clinician Award in 2017, a mark of recognition that he cherishes deeply even years later.

He is prepared for my opening question: What brought him to Singapore?

He was a Gold Medallist with record marks at Calcutta Medical College and undertook his postgraduate studies at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in Delhi.

He went on to obtain his Doctor of Medicine degree and became a Fellow of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists in Britain, where he practised.

However, he wanted to move back to his ageing parents in Calcutta, and did return to the city. But his achievements in India and abroad left his peers and even mentors unmoved. It was time to move on.

What changed his life was a fortuitous interview in London with Emeritus Professor Sittampalam Shanmugaratnam, the legendary Singaporean obstetrician and gynaecologist. The young man was employed immediately.

In Singapore, he faced the perils and promise of the unknown.

“I knew no one here. I knew no Mandarin, Malay or Tamil. I had no referral base to send me patients. But I did not need any of that. I found a country where talent and skills are valued, where clinical and research work is prized. There’s a term for that kind of system: Meritocracy.”

How about life outside work, I ask. “I immediately felt at home here. Singapore is safe and honest and dedicated to excellence. I fell in love with it immediately.”

But Singapore is his second love. His first is his wife, Tapati, whom he met while he was studying at Calcutta Medical College and she was studying Botany at Presidency College, a heartbeat of a street away.

The couple has a cardiologist daughter, Sinjini, educated in Singapore and trained in Australia and Britain, who works in Melbourne.

So far, so good. But what about the future of the human race, including in Singapore? What is to explain the socially suicidal drop in birth rates in this country?

The amiability in Prof. Biswas vanishes. He turns darkly sociological.

“The problem is structural. Women want to be successful in their careers before getting into a serious relationship, let alone marriage and motherhood. There is nothing wrong with this.

“This issue exists across the developed world and not only in Singapore. Yet, everywhere, by the time a woman becomes a mother, she needs to balance many duties, including her accumulated success at work. Couples depend to an extent on their parents to bring up children, except that those parents, too, who themselves delayed parenthood, are ageing.”

Singapore has affordable, full-time domestic workers, who are an economic luxury elsewhere in the developed world. But the cost of living here is high. While Singapore has many pro-natalist policies, and these do help, the country needs a mindset change so that it remains viable demographically, he says. What is that mindset change? A preference for new life.

Prof. Biswas does not give up hope. He has delivered the children of the children whom he had delivered. Life goes on, as it should. “To bring a life into this world is wonderful because every life is unique.”

This, then, is the baby doctor, a man who, even in the prominence that his age has bestowed on him, has not forgotten that he was born one day. He does not believe in retirement because it is impossible to retire from life. “I am not tired,” he says.

I am about to ask him what keeps him young when his handphone rings. “Is she ready to deliver?” he asks. “Yes,” comes the reply.

He walks away briskly towards the maternity ward.

A child is soon born.

Another baby for Singapore.